Turning Point: The Impact of AMLO’s Reforms on USMCA and Nearshoring By: Diego Marroquín Bitar within the Wilson Center

Following the decisive electoral victory by Claudia Sheinbaum and the Morena party on June 2, 2024, her mentor, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) and allies are likely to secure a two-thirds majority in Congress, providing him the power to unilaterally amend Mexico’s constitution.

Before leaving office on October 1, AMLO’s super-majority is planning to implement 18 constitutional reforms that would weaken Mexico’s economic regulatory landscape, degrade its investment climate, dissolve checks and balances, and undermine the country’s ability to fulfill international commitments, including the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). If approved, these legal shifts could seriously challenge North America's long-term competitiveness and nearshoring potential, jeopardize billions in US and Canadian investments in Mexico, and complicate the 2026 review of USMCA.

If approved, these legal shifts could seriously challenge North America's long-term competitiveness and nearshoring potential, jeopardize billions in US and Canadian investments in Mexico, and complicate the 2026 review of USMCA.

Constitutional amendments

a. Judicial Reform

Mexico’s Supreme Court has found several of AMLO’s actions unconstitutional, including efforts to undermine private investment in the energy sector and place civilian public security forces under military control. If approved, the judicial reformwould gradually remove all Supreme Court justices and federal judges, replacing them through popular elections without clear professional qualifications. As presented, this reform would severely weaken the judiciary's role as an independent check on presidential power, leaving judicial decisions vulnerable to political influence and donor interests.

Rather than addressing long-standing issues of corruption and impunity within Mexico’s judiciary, this overhaul could lead to significant delays, pauses, or even retrials in cases involving human rights and private investments in sectors not covered by USMCA.

Rather than addressing long-standing issues of corruption and impunity within Mexico’s judiciary, this overhaul could lead to significant delays, pauses, or even retrials in cases involving human rights and private investments in sectors not covered by USMCA. Under USMCA, US and Canadian investors in Mexico can only pursue claims in the oil & gas, power generation, infrastructure, and telecommunications sectors. Disputes in other sectors require investors to go through Mexico’s domestic court system before seeking arbitration under USMCA.

b. Elimination of Oversight and Regulatory Agencies

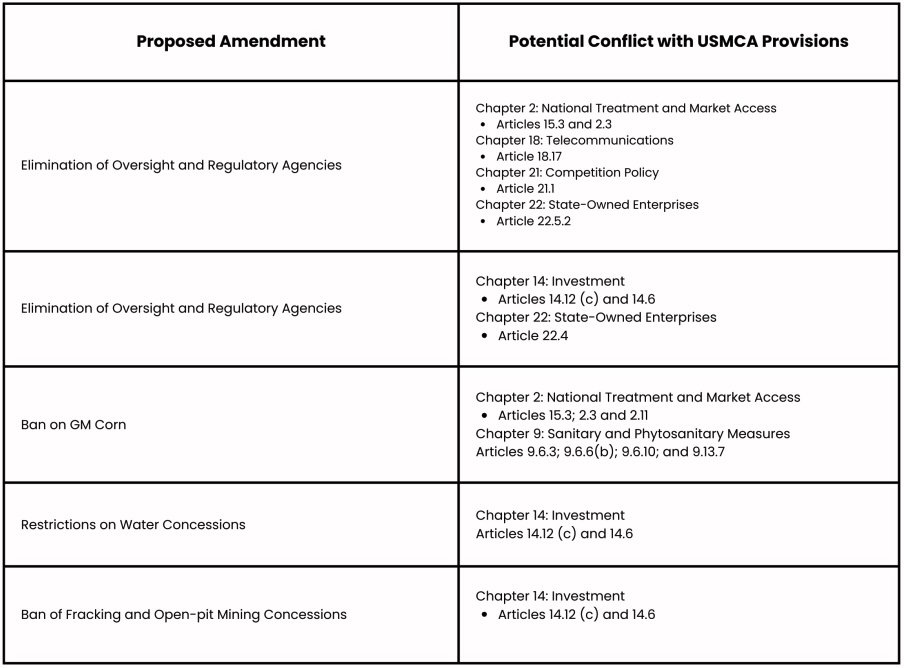

Other proposed reform would dismantle Mexico’s antitrust agency, along with the Federal Economic Competition Commission (COFECE), the Federal Telecommunications Institute (IFT), and the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), transferring their functions to Executive Branch agencies like the Ministry of Economy and the Ministry of Energy. These changes would remove critical checks on presidential power and directly conflict with Mexico’s commitments under USMCA regarding market access, competition policy, and state-owned Enterprises (see Table 1). By eroding legal certainty, the reform would severely hamper Mexico’s nearshoring potential, driving investment elsewhere and weakening North America’s position in the global supply chain.

c. State Energy Industries

One proposal would restrict Mexico’s state-owned utility, the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE), from partnering with private companies for electrical transmission and distribution, while prioritizing CFE market dominance over private firms. By imposing additional restrictions on private investment, this reform conflicts with USMCA’s ratchet clause, which prevents countries from rolling back market liberalization measures once they’ve been implemented (see Table 1). This policy would undermine US and Canadian economic interests and any energy they produce in favor of Mexico’s CFE and its state-owned oil and gas company, PEMEX. Canadian and US firms have invested a combined $34 billion in Mexico’s energy sector, including significant investments in renewable energy projects.

d. Ban on GM Corn and Restrictions on Water Concessions

This proposed reform aims to ban genetically modified (GM) corn for both harvest and human consumption. By introducing trade restrictions without scientific evidence, this reform conflicts with USMCA market access and sanitary and phytosanitary provisions (see Table 1). Mexico, the US's second-largest agricultural export market, imports over $5 billion worth of corn annually. Such a ban could lead to the loss of thousands of US agricultural jobs and threaten food security in Mexico, as domestic production would likely be unable to meet the country’s corn demand.

Another proposed amendment seeks to limit water concessions to firms in regions with scarce water resources, reserving allocations to public entities exclusively for personal and domestic use. By favoring Mexican entities over US and Canadian firms, this proposal would appear to violate USMCA’s National Treatment and Most-Favored Nation provisions (see Table 1).

e. Ban of Fracking and Open-pit Mining Concessions

Constitutional reform proposals to end concessions for open-pit mining and permanently ban oil extraction through fracking conflicts with Mexico’s commitment under USMCA to maintain agreed-upon market openness in these sectors, potentially affecting the operations and ownership of US and Canadian firms (see Table 1). This could lead to millions of dollars in losses, arbitration claims, or trade sanctions from Canada or the United States. Canadian companies, representing 70% of all foreign mining firms in Mexico, are the largest foreign investors in the country’s mining sector.

Risks

If approved, these changes would appear to severely limit Mexico’s growth prospects and its ability to create well-paying jobs in the medium and long-term. The resulting legal issues and business uncertainty could trigger billions of dollars in tariffs if US and Canadian authorities or firms request formal dispute settlement under USMCA, as well as significant economic losses for consumers and workers across North America. In other words, Mexico risks undermining the very conditions that foster job creation and investment growth. Additionally, the potential for trade disputes and economic disruptions could deter new investors and negatively impact nearshoring opportunities.

Ultimately, the reforms could jeopardize the agreement’s renewal and increase the risk of its expiration in 2036, undermining the long-term stability and benefits of the USMCA.

Furthermore, these reforms pose a serious risk to the USMCA’s upcoming review, potentially stalling negotiations with Canadian and US authorities and triggering demands for changes from stakeholders in 2026. This heightened scrutiny could complicate negotiations and result in unsuccessful outcomes in subsequent years. Ultimately, the reforms could jeopardize the agreement’s renewal and increase the risk of its expiration in 2036, undermining the long-term stability and benefits of the USMCA.

Conclusion

AMLO’s reforms represent a turning point that undermines Mexico’s trade and investment commitments under USMCA, making Mexico a less reliable partner for the US and Canada. The proposed legal and institutional overhaul threatens to undermine Mexico’s investment climate for decades, disrupt regional economic integration, and weaken supply chain resiliency at a crucial moment of global economic realignment

Table 1